Ohme new

News

eventproject

CurieuCity Festival

artist residencyproject

Residency Methods | Selected Artist

opportunity

+32 472 237791

Development Director

Nicolas Klimis is a cultural entrepreneur, engineer, arts producer and musician born in Brussels, Belgium. After graduating as a materials science engineer in Brussels in 2013, Nicolas left for London to pursue a master in arts administration and cultural policy at Goldsmiths, University of London. His profound passion for music has led him to work for the European Union Youth Orchestra (London), as a Creative Europe partnership coordinator and for BOZAR (Brussels), as a music producer. In 2016 Nicolas co-founded Ohme, where he now serves as development manager for Ohme Studio, for which he develops a strategy for the production company, finding new project opportunities, fundraising and following production.

Development Director

Raoul Sommeillier is an engineer, a cultural entrepreneur, a scientific researcher and an artist manager. His curriculum and career translate a deep desire to break the boundaries between disciplines and a strong need to combine his many interests in various fields. He holds a double master degree in engineering specialized in mechatronics, an advanced master in technological & industrial management and an upper secondary teaching certificate in engineering sciences. As a PhD candidate in science education specialized in didactics of applied sciences, his researches focus on higher education students’ preconceptions and learning obstacles in scientific fields. He’s also a teacher in electricity and electronics, an artist manager and an amateur musician. He’s co-founder and development manager at Ohme, more specifically in charge of Ohme Academia, the pole entrusted with research, science sensibilization and education.

+32 498 16 31 81

Curator, Artistic Director

With one foot in curation and in art production, and one in cultural policy, Camilla worked in Italy, UK, and Belgium. Always interested in hybridization and crossing of disciplines, Camilla served in art organisations of all sizes as well as with independent artists, focusing on multidisciplinary and multimedia productions. She is co-founder of Saloon Brussels, a network for women working in the art scenes as curators, artists or journalists, as well as in galleries, museums or universities.

Project Manager

Gwenaël Sauvage is a former business engineer graduated at the Solvay School of Economics and Management (Brussels) in 2017. He started his professional career as a strategy advisor for the Ecole polytechnique de Bruxelles, allowing him to strengthen his skills in data analysis, problem-solving and decision-making. After a two years mission, he joined the Ohme at the beginning of 2020 and fulfilled his will to work among a dynamic team in a field he believes in.

Ohme Lab Manager

François is a mechatronics engineer who left a career of power electronics in the space industry to start a co-creation and engineering consulting activity for the non-profit and artistic sectors and for small companies. He joined Ohme in 2020 as technical advisor for the κῦμα artwork in the context of the exhibition Order of Operations at Bozar, and currently works as technical expert and developer for Ohme Lab.

Associate Researcher

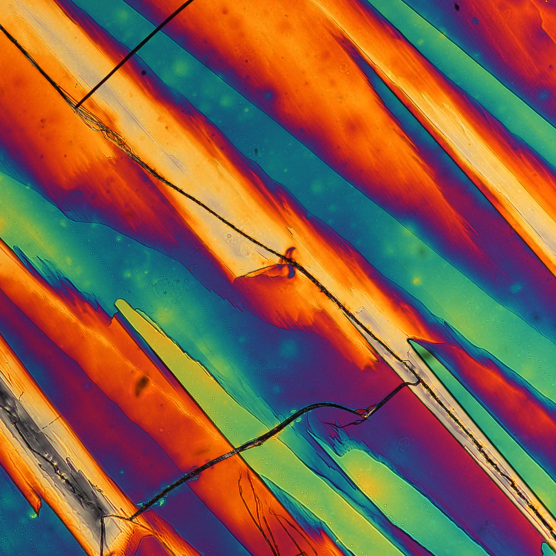

Guillaume Schweicher is a FNRS Research Associate at the Université Libre de Bruxelles and a visiting scientist at the University of Cambridge. He received his Master in Chemical Engineering (2008) and Ph.D. (2012) from ULB, followed by post-doctoral appointments at Stanford University, the University of Cambridge and ULB. His research interests aim at developing novel organic and hybrid semiconducting materials for a greener and more sustainable electronics. For him, microscopy images are bridging the gap between science and art, intriguing and leading to reflection. Since October 2019, he started to interact with Ohme on the establishment of art and sciences contents in accessible, educational and interactive formats. Some of his shots have been presented during the exhibition .IMG | des images qui se regardent and Order Of Operations. So far, the most notable outcome from this collaboration is the realisation of the audiovisual performance Tales of Entropy, staging the irresistible beauty and poetry of an organic compound changing its physical state in a thermal gradient, under polarised light.

Producer

Chloé holds a Master’s degree in Art History and Art Criticism with a specialization in contemporary art from the University of Rennes 2 (FR).

She has a diverse range of experience within the cultural and artistic fields, working with artists, assisting in research projects or producing exhibitions, in cultural institutions, art galleries and organisations in France and Belgium.

She joined Ohme in 2020 to work on the production of the exhibition Order of Operation, driven by her enthusiasm for transdisciplinary projects.

Engineering

Fayssal ISMAILI

Simon HOT

Engineering

Loïc VANHECKE

Engineering

Bartlomiej DREWNOWSKI

Andrew KARAM

Damien RYCKAERT

Romain TAYMANS

Media art

Sam BUSEYNE

Production

Jérémie KAMAY MPOYO

Communication

Chrissi PALLAS

Engineering

Louise DE WOUTERS

Sajl GHANI

Célestin VINCART

Éline SOETENS

Production

Chloé GAUTIER

Engineering

Teo SERRA

Florian JEHIN

Paul SERVAIS

Neurosciences

Athéna GEORGIOU

Production

Annick DUEZ

Engineering

Léonard STEYAERT

The “STEM” acronym was introduced in 2001 by US scientists to group together the disciplines of Science, Technology, Engineering and Mathematics. Well known in the context of education, STEM programmes promote the integration and application of knowledge of math and science in order to create technologies and solutions for real-world problems, using an engineering design approach (Jolly, 2014). These programmes are designed to develop a variety of skills that are essential for success: problem-solving, innovation, communication, collaboration and entrepreneurship, to name just a few.

More recently, a wave of art integration is spreading across the world of STEM : “If creativity, collaboration, communication, and critical thinking – all touted as hallmark skills for 21st century success – are to be cultivated, we need to ensure that STEM subjects are drawn closer to the arts.” Piro (2010)

This push for “STEAM” (Arts + STEM) curriculums derives from the lack of creativity and innovation in recent university graduates in the US. The STEAM initiative offers more than the high-tech skills that are so valued by our society and businesses. Integration of the arts via STEAM empowers our society to foster curiosity and self-motivation, to meld technology and creative thinking, to push personal boundaries and develop individual conceptual methodologies in an innovative manner. Moreover, according to Land (2013), the Arts can enhance STEM skills due to their more divergent approach. They can provide a wider range of opportunities for communication and expression… and what is the purpose of science and engineering if they cannot be transferred, shared and applied?

The integration of the arts in the STEM fields is a recent development in education. According to Ohme, they have been on two sides of the same coin since time immemorial. Science and the arts may be perceived as being very different – even at opposite ends of the spectrum – but the processes used by both fields are very similar. The well-known British mathematician, science historian, dramatist, poet and inventor Jacob Bronowski had already stated in the early second half of the 20th century (1956): “There is a likeness between the creative acts of the mind in art and in science.“

Indeed, the scientific method is a way to explore a problem, form and test a hypothesis, and answer questions. The creative process creates, interprets and expresses Art. In both cases, enquiry lies at the heart of either method (Nichols & Stephens, 2013). In both cases, the “researchers” attempt to bring meaning to their world’s experiences and observations (Honvault, 2010). Moreover, the ability for simultaneous deconstruction of a complex problem using convergent thinking and application of the corresponding solution to the real world using divergent thinking (Land, 2013) involves processes required in both fields of Art and Science. Starting from the following question “What makes some scientists more creative than others?” Root-Bernstein et al. (2008) demonstrated that almost all scientific geniuses between 1902 and 2005 had been proficient not just in science but also in the arts.

Every Ohme’s project is the result of a fusion of skills between artists, designers and scientists, with no restriction on art forms (music, sculpture, digital arts, performing arts, applied arts, etc), or on science branches (formal, natural and social both fundamental and applied). These collaborative meeting points are opportunities for us to study, enquiry, support and develop what Root-Bernstein calls “transdisciplinary interactions”:

“Science and engineering are supposed to be objective, intellectual, analytical, and reproducible so that it is clear when an effective solution has been achieved to a problem. The arts, literature, and music, by contrast, are portrayed as being subjective, sensual, empathic, and unique, so that it is often unclear whether a specific problem is being addressed, let alone whether a solution is achieved. It therefore comes as a considerable surprise to find that many scientists and engineers employ the arts as scientific tools, and that various artistic insights have actually preceded and made possible subsequent scientific discoveries and their practical applications. These transdisciplinary interactions must cause us to reconsider how we think about innovation.”

The term “ArtScience” is relatively recent. It has been employed by the first time by Todd Siler in his book “Breaking the mind barrier” (1990).

Since then, more and more artists, researchers, philosophers, engineers and designers take a firm grasp of this notion and draw on it to think about new ways to connect people with various backgrounds, to explore new ideas, to break the boundaries between disciplines.

This growing emergence of transdisciplinarity helped Siler and colleagues to propose a more well-defined definition, what they called the ArtScience Manifesto:

ArtScience, in sum, connects. The future of human- ity and civil society depends on these connections. ArtScience is a new way to explore culture, society and human experience that integrates synesthetic experience with analytical exploration. It is knowing, analyzing, expe- riencing and feeling simultaneously.

Talks and videos

Founded in 2017 by a team of engineers and cultural professionals, Ohme is a Brussels-based ArtScience production, research and education organisation. It is divided into three poles:

Ohme Studio a production company that develops installations, performances, events and exhibitions, and accompanies artists in the development of their projects.

Ohme Academia an educational and research institute that develops academic programmes and encourages transdisciplinary research between art and science.

Ohme Lab an R&D centre that develops technologies and offers design, prototyping and manufacturing services for artists and designers.

Ohme investigates the boundaries between artistic and scientific disciplines, contributing to the development of new conceptions of interdisciplinarity, with a keen interest in co-creation, knowledge sharing, research and the breaking down of barriers between disciplines, mentalities and audiences. This involves exploring new practices of scientific mediation, artistic creation and innovation, through collaborative and transdisciplinary practices.

Bringing together established and emerging artists, scientists, researchers and students, Ohme produces artscience projects and coordinates academic programmes on a variety of topics, from physics to music, from neuroscience to digital arts, from design to social sciences.

Moving from the visual arts to the performing arts, from the natural sciences to the humanities, Ohme’s initiatives are transversal and attempt to question our relationship to societal issues, in the light of the arts, the sciences and their pluralism and synergy.